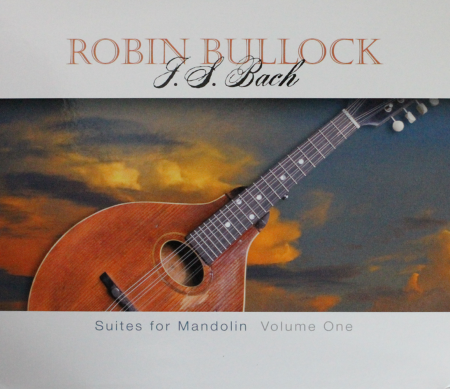

Description

Suite No. 1 (BWV 1007)

1. Prelude

2. Allemande

3. Courante

4. Sarabande

5. Minuets I & II

6. Gigue

Suite No. 2 (BWV 1008)

7. Prelude

8. Allemande

9. Courante

10. Sarabande

11. Minuets I & II

12. Gigue

Suite No. 3 (BWV 1009)

13. Prelude

14. Allemande

15. Courante

16. Sarabande

17. Bourées I & II

18. Gigue

Liner Notes

They’re not suites “for” mandolin, of course – the works presented here are the first three Suites for Solo Cello, BWV 1007-1009, adapted for solo mandolin. Johann Sebastian Bach never composed for the mandolin (although his contemporary Vivaldi frequently composed for its gut-strung predecessor the mandolino, an instrument which apparently never attracted Bach’s attention). Nevertheless, transcription of music was a common practice during the Baroque era, and Bach himself was one of music history’s great transcribers, routinely transferring both his own and other composers’ work from one instrument or ensemble combination to another, modifying it as necessary in the exploration of different timbres and registers. Thus Partita No. 3 in E Major for solo violin also exists as Lute Suite No. 4 (with its Prelude showing up in a couple of cantatas as well), the trio sonata for two flutes and continuo is also Sonata No. 1 in G Major for viola da gamba and harpsichord, and so on, to the point that the legendary pianist and Bach specialist Glenn Gould spoke of Bach’s “sublime instrumental indifference.” In the two-and-a-half centuries since Bach’s death, transcriptions and adaptations of his work have run the gamut from solo piano to full symphony orchestra, from saxophone ensembles to steel drum bands to jazz and rock groups (Jethro Tull’s 1969 hit “Bourée” coming straight from the E Minor Lute Suite) and virtually every other imaginable instrumental setting. An interpretation of the unaccompanied Cello Suites on mandolin, an instrument similarly tuned in fifths and related to the lute, therefore seems a fairly logical choice; in fact, I would even venture to call it well within the spirit of Bach.

The Cello Suites, one of the Baroque era’s unquestioned masterpieces, carry with them a number of mysteries. Bach’s original manuscript no longer exists, leaving us to rely on two (slightly differing) source manuscripts, one by Bach’s second wife Anna Magdelena, a singer and keyboard player, and the other by a friend and student of Bach’s, Johann Peter Kellner. Neither allows the Suites to be dated with precision, but they’re generally assumed to have been composed during Bach’s tenure as Kappellmeister to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen between 1717 and 1723 – the only period in Bach’s career when his responsibilities didn’t include the composing of liturgical music, leaving him free to focus on instrumental composition for the small but carefully chosen court ensemble he directed as Kappellmeister. (Also dating from this period are the Brandenburg Concertos, the violin and harpsichord sonatas, and the Cello Suites’ counterpart for unaccompanied violin, the six Sonatas and Partitas.) This being the case, they may have been composed for, and first performed by, one of the two virtuoso cellists in Prince Leopold’s employ, Christian Bernhard Linike or Christian Ferdinand Abel. On the other hand, the surviving manuscripts don’t actually specify cello as the intended instrument (the cover page of the Anna Magdelena manuscript titles the cycle “6 Suites á Violoncello Solo senza Basso,” but that page was added by a later editor), and an intriguing alternate line of speculation has arisen that Bach himself – a skilled violinist and violist in addition to his genius at the keyboard – might have been the original performer, playing the Suites on a four-string violoncello da spalla or some other baritone-range viola-like instrument tuned to cello pitch…

The six suites are consistent in their structure: each consists of the standard four dance-inspired movements of a Baroque suite, allemande, courante, sarabande and gigue, preceded by an improvisatory-sounding prelude that sets the mood for the entire suite, and with a pair of galanteries (minuets in the first two suites, bourées in the next two and gavottes in the last two) inserted between the sarabande and the gigue. The result is a perfectly-paced build of spirit and intensity through the first three movements, a sudden downshift at the halfway point with the arrival of the sarabande, and a second gradual build to the final climax of the gigue. Nevertheless, despite this surface uniformity each suite displays its own individual character – I personally hear No. 1 as innocent and wistful, No. 2 as brooding and angry and No. 3 as quietly joyous – and many surprises await the listener throughout the cycle, such as the five stark, uncompromising chords that conclude the prelude to No. 2, the playful series of false endings concluding the prelude to No. 3, the unexpected flurries of whippingly fast notes lurking in both the allemande from No. 2 and the courante from No. 3, or the almost rock-and-roll double-stop riffs that burst out in the gigue from No. 3.

Astonishingly, the Cello Suites were all but forgotten by the late 19th century, when a young Pablo Casals discovered them in a Barcelona music shop. His subsequent career as the world’s most celebrated cello virtuoso brought the Suites to public attention, and he made the first recording of the complete cycle in the 1930s on a series of 78 RPM records (still available on CD). Since then, the Suites have been in the repertoire of virtually every cellist, as well as players of many other instruments; recordings exist of the Suites interpreted on viola, string bass, lute, harp, classical guitar, electric guitar, marimba and even trumpet. To the best of my knowledge, however, this CD and the second volume to follow will constitute the first complete recording of all six Suites on mandolin. (I’d be happy to be corrected on this point; if you know of others, drop me a line at www.robinbullock.com.) The mandolin’s g-d’-a’-e” tuning necessitates transposing the three Suites on this CD up an octave and a fifth, and I find that (for me, at least) whatever they may lose in gravitas when moved from cello to mandolin they make up for in an ethereal lightness, almost as if otherworldly music is being overheard from some mysterious, enchanted realm.

A guiding intention in my adaptation of these works has been to create the impression that they could have been composed for the mandolin – or better still, to make the listener forget about the instrument altogether; as always with Bach, the architecture of the music transcends the specific instrumentation. I’ve created my own mandolin-specific fingerings throughout to compensate for the instrument’s limited sustain, and occasionally added harmony voices implied in the original score, a practice that can be traced back to Bach himself adapting his solo violin works to keyboard. (I’ve also discovered that the mandolin’s ability to voice entire chords can even give it something of an advantage at times over the cello, heretical though that no doubt sounds.) What I have not tried for is any “definitive” interpretation, because regardless of instrumentation, a definitive interpretation of Bach is simply not possible. The music is too endlessly rich, revealing more treasures the deeper one delves into it; all a musician can do is approach it with humility and offer the listener an individual interpretation in the here and now, inevitably influenced by those who came before and by the musician’s own life experience, emotions, culture and time. Bach speaks to us in his own late-Baroque musical language but he speaks just as powerfully in the present moment, and to paraphrase theater director Peter Brook’s comment about Shakespeare, if he’s valid at all he’s valid right now.

Robin Bullock

Black Mountain, North Carolina

Fall 2016

About the Mandolins

The mandolins heard on this recording are all vintage Gibson A models, a different one for each suite. I began this project by recording Suite No. 1 on a circa 1920 Gibson A I’ve owned since 2007, affectionately nicknamed The Feral Cat (because its previous owner maintains that it only purrs when it’s in my lap). When Feral Cat needed some minor repairs in early 2016, however, I realized I didn’t have any worthy alternate instruments and went on something on a mandolin-buying rampage, the prizes from which were two more A models from 1921 and 1909. The 1921 got the name Coyote, in memory of a beloved cat (a real one), and Coyote’s beautifully rich tone is heard on Suite No. 2; the 1909 became Black Beastie (because it’s black, but has a dramatic scar down its headstock that makes the name Black Beauty seem not quite right), and Beastie’s extraordinary power and window-rattling bass is heard on Suite No. 3.

Many thanks to instrument setup/repair masters Randy Hughes at Hughes String Instruments, Fairview, North Carolina, Tom Fellenbaum at Acoustic Corner, Black Mountain, North Carolina, Dave MacCubbin at Appalachian Bluegrass Shoppe, Catonsville, Maryland, and Mike Andrews at Meadowood Music, Blandon, Pennsylvania for bringing these wonderful instruments to their fullest potential. RB